SOUNDTRACK: THURSTON MOORE-Trees Outside the Academy (2009).

SOUNDTRACK: THURSTON MOORE-Trees Outside the Academy (2009).

Thurston Moore is a founding member of Sonic Youth. He’s put out several solo albums over the year, although I feel like only two really “count,” Psychic Hearts and this one.

Thurston Moore is a founding member of Sonic Youth. He’s put out several solo albums over the year, although I feel like only two really “count,” Psychic Hearts and this one.

Anyone familiar with Sonic Youth knows that the band has pop sensibilities but that they bury their poppiness under layers of guitars or noise or other things. And everyone knows that Thurston is one of the main noisemakers (you don’t put screwdrivers under you guitar strings and expect to break the top 40). So it may come as some surprise just how accessible and poppy this record is. In fact, I first heard one of the songs on a Radio compilation (true it ‘s an awesomely hip radio station…88.5 WXPN Philadelphia), but I couldn’t get over how supremely sweet the song “Fri/End” was.

And, although there are a few noisy moments on the disc (Thurston loves his feedback squalls), the large majority of the disc is really catchy almost folky indie music (acoustic guitar and violins!). But it’s important to mention that Dino Jr’s J. Masics is also on hand and that he plays some wild solos on about half of the tracks (most of the longer instrumental pieces). Like on the the title track, a nearly 6 minute instrumental that has a great melody; the middle section just screams with a great Mascis solo.

Okay, so technically that’s not the final track. “thurston @13” is a home recording from when the man was 13 years old. It’s him recoding various things around his house (spraying Lysol, dropping coins) with hilariously pompous 13 year old narration. It reminded me of me when I was kid and got hold of the family tape recorder–I used to record myself doing all kinds of weird kid things (I wish I still had those tapes). It’s just silliness, but I really enjoyed it.

Even if you’re not particularly a fan of Sonic Youth, this is a worthwhile addition to any record collection.

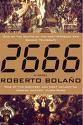

[READ: Week of January 25, 2010] 2666 [pg 52-102]

As this second section opens, we see Norton and Morini still together during his visit. She takes him to an area of London that has become trendy, and features great restaurants. She relates the story of the first famous person to move there, a painter named Edwin Johns. Johns is famous mostly for one painting but its notoriety led it to sell for a ton of money.

As this week’s reading draws to a close, we get a wonderful parallel story about this very painter. Espinoza, Morini and Pelletier travel to the sanitarium where the painter is currently residing. Morini is compelled to ask the man one very specific question.

For in the story that Norton related, she revealed that Johns chopped off his hand, had it embalmed, and placed it at the center of his one masterpiece painting. This painting became the centerpiece of a very successful exhibition. Morini is queasy during Norton’s story and when he later confronts Johns at the sanitarium, he demands to know why Johns cut off his hand. As this section draws to a close, Johns reveals to Morini that the answer is, simply, money.

But fear not, Archimboldi fans, the man is not forgotten, and the next revelation about him comes from an unlikely source. A Serbian writer reveals some tactile information that sheds light on Archimboldi himself. One of the details is that he bought a plane ticket flight but never showed up for the flight. The Serbian writer believes it was because he canceled the flight under the pseudonym and then rebooked the flight under his real name. Although Pelletier published the article in his journal, further scrutiny by himself and Espinoza lead them to doubt its credibility or use.

But more upsetting to the two of them is Norton’s desire for a change. She wishes to get away from her life, from London and from the two men. So she invites them over and reveals this truism to them. Several months go by with them respecting her desire for distance, although neither one thinks she means it. But one day they decide that they will both visit her, together.

When they arrive at her flat, with flowers in hand, they see that she has a man in her apartment, Alex Pritchard. He is a teacher, but he quickly proves to be intellectually inferior to our pair. Espinoza even calls him a badulaque (“a fool of no consequence”–and my favorite new insult!)

Now, sexual tension is all over the place. They need to know how she feels about Pritchard. She doesn’t know. Nevertheless, they pledge themselves to Norton, and promise they will wait for her if she changes her mind.

In a taxi ride together, they discuss all of these possibilities. The taxi driver, a Pakistani man, listens intently to their conversation and then throws in his two cents: she is a whore and they are her pimps. This goes over as you might expect, and the two men pull the driver out of the cab and proceed to kick him to within an inch of his life. All three of our heroes feel an incredible rush of emotion over this, likening it to an orgasm. But Norton, once her senses come back to her, is repulsed and horrified by what has happened and that her two friends could come to this. The cabbie is okay, but suffered serious damage.

She asks them not to talk to her for a while. Both men return to their homes and, after processing what they’ve done, they engage in an extended course of soliciting prostitutes. Pelletier decides that he likes one in particular: Vanessa. She is married and her husband knows what she does. He starts buying her gifts, and ultimately he visits her house, [although, really Pelletier, what good could come of that?]. Her husband and son are home, and he just feels uncomfortable by the reality he sees there. And that pretty much ends his liaison with her.

Meanwhile, back in Madrid, Espinoza speeds through many many different prostitutes, of all different races and colors (he is intrigued that they include their nationalities in their ads). He doesn’t get attached to any of them.

During all of this Norton business, the two men had more or less given up on their research. Even the thought of Archimboldi left them cold. But after they get the massive amounts of sex out of their system, they feel refreshed and ready to get back to work.

Eventually, the two of them also feel ready to reach out to Norton again. So they head to London for a visit. The dinner is cold and rather stilted, so Espinoza decides to relate the story of when he, Pelletier and Morini (at Morini’s bidding) went to Switzerland to visit a famous painter living in a sanitarium (see above for how that goes).

After visiting the Sanitarium, and hearing the truth from Johns, Morini basically can’t handle things. So he takes off in the middle of the night and doesn’t tell either of his traveling friends anything. They’re quite worried about him. They call him for several days with no luck, and they start to panic. Finally, he picks up the phone, where he reveals that he spent the last several days in London, with Norton.

[I really need to see the official timeline for this story to piece out exactly the whens and wheres of this rather convoluted and overlapping tale.]

This would have made a natural ending point for this week, but such is the way when you have to impose page numbers. And so…

The story jumps briefly to a seminar in Toulouse where we are introduced to a young Mexican student named Rodolfo Alatorre. [At this point I’m starting to wonder why some characters get named and others don’t]. He is totally blown off by Norton, Espinoza and Pelletier. However, Morini finds him less disagreeable and they have a lengthy chat. The conversation turns to Archimboldi. Alarorre reveals that a friend of his met Archimboldi just the other day.

The friend, known as El Cerdo (The Pig), received a call in the middle of the night. Archimboldi was being interrogated by police in a hotel near Mexico City. Although the police didn’t steal anything(!) they did want money from him. [I have no idea why A) Archimboldi was with the police or B) El Cerdo was called about the happenings…. I’m sure more will come out later, and it seems fairly clear that El Cerdo and Archimboldi are acquaintances but that’s all I get from it]. El Cerdo and Archimboldi decide to go for drinks (even though its 2 in the morning and he has a flight at 7). El Cerdo finally asks Archimboldi, “Listen weren’t you supposed to have disappeared” to which Archimboldi just smiles.

And on that cliffhanger (maybe it is a good place to stop after all) we finish the week’s read.

COMMENTS

It’s strange to be 11% of the way through a novel (thanks Infinite Zombies for this little calculator) and still not be sure exactly where all this is going (although I don’t mind). Or, more to the point, to know that some things are coming up but to be really unclear how they are going to get there. I’m not even going to speculate wildly about the proceedings.

So far, I really enjoy the book, and I’m very interested in what’s going to happen next. I also find the 50 page a week limit to be a limit too low, as I could easily read more (it seems a pretty quick read thus far), but I’m going to stick to the schedule.

The next part is called The Part about Amalfitano, so I assume that it will be a very different piece of writing than this one. And I’m looking forward to getting to it, but first, I’m very curious to see how this book will end, and indeed if the book would work as a self- contained unit. I mean, if he had published these books separately could you have just read one of them and felt satisfied? I’ll find out this week.

For ease of searching I include: Bolano.

You are very correct about The Part About Amalfitano being very different from the first section. I can’t wait until we get to that part because things really start to get weird!

Each of the parts was originally intended to be published separately. One a year, or something like that. Bolano wanted to be sure that his family would have enough income to survive after his death. In fact, in the novel’s Note to the First Edition, Bolano mentions that the parts could even be read out of order.

Whether you would have been satisfied with just one of the parts – probably not. At least, I wouldn’t have been satisfied.

Thanks Brooks. You’ve got me very excited to read part two. I just read a short story of his in The New Yorker and it seems so different in style to Part 1 of 2666. And this style from the short story is what I think of when I think of Bolano’s writing: long almost stream of consciousness pieces. So, this first section has been much easier than I imagined.

Although I can’t imagine each of these books as separate items in themselves, it’s interesting to think about reading them in any order. I’m quite excited for the rest of the book.