SOUNDTRACK: ELVIS COSTELLO AND THE IMPOSTERS-Momofuku (2008).

SOUNDTRACK: ELVIS COSTELLO AND THE IMPOSTERS-Momofuku (2008).

I’ve enjoyed Elvis Costello for many years. I’m not a die hard fan, but his Best of is often in play in our house. I got into a little phase where I was buying a bunch of his things, but that has more or less subsided now. And, since he has become somewhat more classically oriented I’ve basically just stopped listening. So, when I heard that on this release he was returning to his rocking days, well, I figured I’d give it a go.

I’ve enjoyed Elvis Costello for many years. I’m not a die hard fan, but his Best of is often in play in our house. I got into a little phase where I was buying a bunch of his things, but that has more or less subsided now. And, since he has become somewhat more classically oriented I’ve basically just stopped listening. So, when I heard that on this release he was returning to his rocking days, well, I figured I’d give it a go.

My initial reaction was somewhat muted as I thought I’d be getting a whole disc of “Pump It Up”s and “Oliver’s Army,” which you don’t. But what you do get is almost  a condensation of his albums from My Aim is True through to about Spike (a long period, granted, but it makes sense).

a condensation of his albums from My Aim is True through to about Spike (a long period, granted, but it makes sense).

The album opens with a few rocking tracks that hearken back to his earlier punkier songs. Although “No Hiding Place” sounds “fuller” than his 1970s records, it doesn’t sound out of place with classic tracks. But really, it’s “American Gangster Time” that brings back that classic Costello organ sound. This track could have been written thirty years ago and would easily fit on any Best Of. “Harry Worth” hearkens back to Costello’s ballads. It’s a bit less punchy than say “Everyday I Write the Book,” but the wit is in high marks. “Drum & Bone” has the fun tongue twisting chorus of “I’m a limited, primitive kind of man.” One of the highlights is “Flutter & Wow” a potentially timeless love song that somehow rings of Van Morrison. It’s really stellar track.

Side Two (his phrase not mine) starts off rocking once again, and, while “Stella Hurt” rocks pretty hard, it tends to drag on a bit long. But it quickly moves to another beautiful ballad, “My Three Sons.” The album ends with “Go Away” another organ-heavy rocker.

And so the album is mixed nicely with some rockers and ballads balancing out the totality of the disc. Lyrically, the songs are tight and witty. The ballads are lovely. I don’t know if Costello’s work with more more mature performers has affected him a lot, but it certainly hasn’t impacted his ability to write good rock songs. Welcome back Elvis.

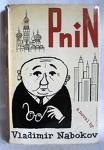

[READ: November 20, 2008] Pnin

I harp on the appearance of book covers a lot. I know that the contemporary covers are fine and they try to retain a consistency for each author. But, I love this early cover. I especially like that there’s an artist’s rendering of Pnin himself. It really paints an immediate picture of the man.

I bought my copy of Pnin many, many years ago, probably right after I had read and enjoyed Pale Fire so much (I had a coworker who really loved Nabokov and insisted that I keep reading him). It has been sitting on my bookshelf for all this time just waiting for me to read it. About three months ago, I decided I would like to read all of Nabokov’s works, so I brought it out of the basement and left it next to my bed. Then, I got the October 2008 Believer. The first article, “Amerikas,” by Adam Thirwell (excerpted here) was about novels and translations. And, since Nabokov is a novelist and translator, he was included in the article. About seven pages into the article is an excerpt from Pnin. And the excerpt was quite amusing, so, I took it as a sign to read Pnin next.

The most fascinating thing to me about the book is that is told by a narrator whose name we never learn, and whom we don’t actually meet until the last chapter. In fact, the story seems like a basic third person story until a few pages in when the I of the narrator rears its head and you realize that there is someone telling you this story. This narrator claims to have known Timofey Pnin for years, and to have met on a few occasions (which Pnin denies).

Pnin is a short book (less than 200 pages). It concerns Dr. Timofey Pnin (a name which is mispronounced throughout the book but which is never pronounced correctly, so I’m not even sure how to say it) who is an assistant professor of Russian at Waindell College. His classes are poorly attended, and he is barely even registered as a teacher by the university itself.

As the book opens, we learn that Pnin is on the wrong train. He is off to a lecture at the Cremora Women’s Club (at which he is upstaged by the announcement of the guest who is scheduled to lecture next month), but he read an old schedule, and boarded an express train by mistake. The whole slapstick proceedings of his getting lost and trying to find his way to his lecture (leaving behind his luggage, recalculating his new time of arrival, etc) are quite funny.

Pnin has been at Waindell College for nine years. Every semester he finds a new place to live: usually an apartment or sometimes an empty room in someone’s house. He simply cannot tolerate the close quarters, the lack of solitude, and the noise of living with someone, so he continually seeks new accommodation. The bulk of the second chapter has him staying with a colleague (Professor Clements) and his wife, a nice couple who let him their daughter’s room while she is at college.

While here, he hears from his ex wife, Liza. Liza left him for Dr Eric Wind, but after many years of silence she hunts him down. Pnin anxiously awaits to hear why she has called upon him, hopeful that some good can come of this. Sadly for Pnin, she just wants him to financially support her son Victor (who is not Pnin’s son). The relationship proves to be somewhat beneficial to Pnin, despite the obvious bizarreness of it. (His closeness with Victor is a very humanizing moment, and a cause for a very emotional scene near the end of the party coming up next).

Ultimately Pnin moves into a house, his own house! (which he considers purchasing). To celebrate his status as a home-renter, he throws a big faculty party. And that party takes up most of the next-to-last chapter. I was happy to see that the party turns out to be a success (I feared that it would be a disaster, what with him cooking and arranging it for himself, and with the guests’ less than thrilled to be attending). It is only at the end of the party that Pnin learns the bad news that… well, you’ll have to read it to find out.

Nabokov can be a difficult writer (see Transparent Things), but his command of the English language (which has to be his third or fourth language by my count) is astonishing. There are puns, and twists of language, and the way that Pnin mangles the English language (calling Prof Wynn: Vin, calling Thayer’s wife, Joan: John) is all very funny indeed. Plus, Nabokov throws in all manner of Russian words (as if the narrator is telling this story to a Russian reader who would need to know, for instance, which form of a Russian word is being used).

The story also has a lot of fun with academics. There is a whole subsection of a chapter devoted to how the chairperson of the French department not only cannot speak French, but will not hire anyone who can read French because they don’t teach by reading in the department. The party is a wonderful opportunity for Nabokov to mock the way academics mingle at parties as well.

Despite its length, Pnin is not an easy book. I know I got lost a few times in what was happening (this is mostly due to the fact that I am reading at lunch, and am probably not devoting as much attention to the book as I should). In fact, there’s a whole story about Pnin having all his teeth removed that I feel like I missed the reason behind. Another complication is that the narrator’s role in telling the story is undermined not only by Pnin himself (who at a party tells the other party-goers not to believe anything that the unnamed narrator says), but by the final lines of the book (in which another colleague calls into question whether or not the narrator knows what he’s talking about).

Nevertheless, or perhaps because of this, I found the book very enjoyable. And, even with many questions left unanswered, I enjoyed the way the book ended. It was a beautifully rendered scene, and the final line is a very funny twist on the book that you’ve just read.

Leave a comment