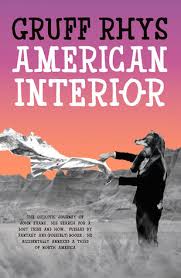

SOUNDTRACK: GRUFF RHYS–American Interior (2013).

SOUNDTRACK: GRUFF RHYS–American Interior (2013).

Gruff Rhys was (is?) the singer and composer in Super Furry Animals, a fantastic indie-pop band from Wales. After several years with SFA and several solo albums, Gruff decided to do something a little different. Actually, everything he does is a little different, as this quote from The Guardian explains:

Gruff Rhys was (is?) the singer and composer in Super Furry Animals, a fantastic indie-pop band from Wales. After several years with SFA and several solo albums, Gruff decided to do something a little different. Actually, everything he does is a little different, as this quote from The Guardian explains:

“The touring musician can feel like the puppet of consumer forces,” he writes, bemoaning the way that “cities have now been renamed ‘markets’ and entire countries downgraded to ‘territories'”. So, over the last five or so years, he has come up with the idea of “investigative touring”: combining the standard one-show-a‑night ritual with creative fieldwork. In 2009, he went to Patagonia to trace the roots of a disgraced relative called Dafydd Jones, and the Welsh diaspora in South America more generally, and played a series of solo concerts, as well as making a film titled Separado!. Now, Rhys has reprised the same approach to tell another story, and poured the results into four creations: an album, another film, an ambitious app, and this book – all titled American Interior, and based on the brief life of John Evans: another far-flung relative of the singer, who left Wales to travel to North America in the early 1790s.

So yes, there’s a film and a book and this CD. This album is a delightful blend of acoustic and electronic pop and folk. Rhys’ voice is wonderfully subdued and with his Welsh accent coming in from time to time, it makes everything he sings somehow feel warm and safe (even when it’s not). Rhys creates songs that sound like they came from the 1970s (but better), but he also explores all kinds of sonic textures–folk songs, rocking songs, dancing song, even songs in Welsh.

“American Exterior” is a 30 second intro with 8-bit sounds and the repeated “American Interior” until the piano and drum-based (from Kliph Scurlock) “American Interior” begins. It’s a catchy song with the repeated (and harmonized) titular refrain after each line and it’s a great introduction to the vibe of the record. It’s followed by the super catchy stomping “100 Unread Messages” which just rocks along with a great chorus. You can see Gruff “composing” the lyrics to this in the book.

“The Whether (Or Not)” introduces some electronic elements to this song. It’s basically a great pop song with splashes of keys and some cool stabs of acoustic guitar. “The Last Conquistador” and “The Lost Tribes” are gentler synthy songs, as many of these are. “Liberty (Is Where We’ll Be)” returns to the acoustic sound with some really beautiful piano.

“Allweddellau Allweddol” (English translation: Key Keyboards) is the only all-Welsh song on the record and it romps and stomps and is as much fun as that title suggests it would be. There’s even a children’s choir singing on it (maybe?).

“The Swamp” is a simple electronics and drumming pattern which leaps right into “Iolo” one of the most fun songs on the record. It’s a nod to the Welsh poet who inspired but backed out of Evans’ expedition at the last-minute but also a rollicking good time with the chanted “yoloyoloyoloyolo” and great tribal drums from Kliph.

The end of the album slows things down with “Walk Into the Wilderness” a slow aching ballad and the final two animal-related songs. “Year of the Dog” is kind of a mellow opus when it is joined by the instrumental coda “Tiger’s Tale.” Both songs feature goregous pedal steel guitar from Maggie Bjorklund.

Gruff Rhys is an amazing songwriter. He could write the history of an obscure Welshman and still get great catchy songs out of it. And that’s exactly what he’s done here.

[READ: December 2018] American Interior

How to explain this book?

I’ll start by saying that I loved it. I was delighted by Rhys’ experiences and, by the end, I was genuinely disappointed to read that Evans’ trip didn’t pan out (even though I knew it didn’t). The only compliant I have about the book is that I wish he had given a pronunciation guide for all of the welsh words in there, because I can’t even imagine how you say things like Ieuan Ab Ifan or Gwredog Uchaf or Dafydd Ddu Eryri (which is helpfully translated as Black David of Snowdonia, but not given a pronunciation guide). But what about the contents?

The subtitle gives a pretty good explanation but barely covers the half of it.

Here’s a summary from The Guardian to whet one’s appetite for Rhys himself and for what he’s on about here:

[John] Evans was a farmhand and weaver from Waunfawr on the edge of Snowdonia, who was in pursuit of something fantastical: a supposed tribe of Welsh-speaking Native Americans said to live at the top of the Missouri river, who were reckoned to owe their existence to the mythical Prince Madog, a native of Gwynedd who folklore claimed had successfully sailed to the New World in 1170. In 1580, this story was hyped up by Elizabeth I’s court mathematician and occultist John Dee (born of Welsh parents), in an attempt to contest the Spanish claim to American territory. Two centuries later, with the opening of new frontiers, talk of a tribe called the Madogwys and “forts deemed to be of Welsh origin” began to swirl anew around Wales and North America, and became tangled up in the revolutionary fervour of the time, along with a radical Welsh spirit partly founded in nonconformist Christianity.

All this was moulded into a proposal made by a self-styled druid named Iolo Morganwg (“a genius”, but “also a fraud of the highest order”, says Rhys), who “called for the Americans, in the light of Madog’s legacy, to present the Welsh with their own tract of land in the new country of the free, so that the Welsh could leave their condemned royalist homeland”. Morganwg stayed put in Cowbridge, near Cardiff (the site of his “radical grocery” shop is now occupied by a branch of Costa Coffee), but Evans was inspired by his visions, and eventually set sail.

Rhys goes on a “journey of verification”, following Evans’s route from Baltimore, through such cities as Pittsburgh and Cincinnati, and then up the Missouri river to the ancestral home of the Mandan tribe of Native Americans, who had been rumoured to be the Welsh-speakers of myth, and among whom Evans lived, in territory argued over by the British and Spanish. Along the way, he does solo performances built around music and a PowerPoint-assisted talk about Evans’s story, keeps appointments with historians, and also tries to glimpse the America that Evans found through the cracks in a landscape of diners, what some people call “campgrounds”, and Native American reservations.

The Guardian’s review also talks about why the book works:

The result is a then-and-now narrative that could easily go wrong, but that actually soars, thanks to three things: the strength of Rhys’s writing, his talent for finding the extraordinary among the mundane and his grasp of the subject. Some of American Interior‘s charm lies in juxtaposition, not least when it comes to the differences between the epic drama of Evans’s life, and Rhys’s rather more bathetic experiences. In a letter written in July 1797, Evans described quite amazing woes: “Now lost in the infinite wilderness of America – Oh unsufferable Thirst and hunger is an amusement in comparison to this … 3rd day here my fever returned … Travelled several miles in water from the hip to the Arm Pitt, amongst a numerous crowd of the biggest water reptiles I ever saw.” Rhys has to cope chiefly with minor traffic accidents, dental problems and the occasionally ramshackle nature of his gigs. The gently comedic tone that arises from that contrast is assisted by Rhys’s companion throughout his trip: a three-foot Sesame Street-esque “avatar” based on his speculative sense of what Evans might have looked like, who eventually seems to acquire his own personality.

It also helps, I’m sure that Rhys is a descendant of Evans. But yes, Gruff Rhys and a puppet (created by SFA’s go-to artist Pete Fowlers) set out across America with obviously a few other people (like film director Dylan Goch,) in tow, to recreate the 1790 journey of John Evans.

Rhys lets us know right from the start that Evan’s whole trip was bonkers and a failure (but not actually a failure). The very premise that there were Welshmen in America was nonsense created by historical revisionists. And yet Evans went anyway. It’s hard to even imagine that he was a 22-year-old travelling in America for misguided reasons (something 22 year olds do all the time now, I suppose).

But the failure of Rhys’ mission neither deters Rhys nor should it deter the reader. Because Rhys is an amusing storyteller and he delights in the unexpected. Just the first chapter’s title alone should be intriguing: “Of the Improbability that I Would Ever Encounter a First Nation American Sagebrush Ritual in the Canton District of Cardiff.”

The first act basically sets everything up. How Gruff wanted to take the trip, who he talked to to get everything set up and a lot about Evans himself. Like what he might have looked like and just how Rhys ended up with a puppet of Evans

Act Two includes historical documents (letters from 1792 about the preparations for the trip) and then Evans’ and Rhys’ time in America. Unlike Evans it was not Rhys’ first trip to America, but it was his first time to many of these places. I am only bummed to find out that he played PhilaMoCA on this 2012 tour where I would have loved to have seen him. His support act was Gwyn A William’s film Madoc: The Making of a Myth.

I love that as these chapters progress you can see him writing lyrics for what would become “100 Unread Letters.”

You zoomed up to Philly/They’d taught you to make maps / They showered you with piety / and pitied any lapse

He travels from Baltimore to Philadelphia and on to Pittsburg (including Welsh named towns like Nanty Glo). Then to Cincinnati and then Kentucky. Rhys plays small shows and interacts with locals (some of whom were clearly contacted ahead of time). Then on to St Louis (where Evans was incarcerated on his trip). Then to Kansas City and Omaha, and dealings with Omaha tribe of Native Americans. One thing I really liked about the book was Rhys’ careful attention to respecting Native Americans in ways that most Americans do not. So he calls the Native Americans by their Native names–the Omaha are actually the Umoⁿhoⁿ (he performs a concert at their high school with the White Tail Singers who “bang a large shared floor-bound drum in unison and then chant beautiful Umoⁿhoⁿ-language songs some traditional some more recent). It’s also weird that I had to read a book fro ma Welshman to learn that Sioux is “an offensive catch-all term coined by their enemies the Ojibwe and mispronounced by the French who used it to refer to numerous nations belonging to the same linguistic group–the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota and their multitude of descendant tribes.”

Rhys talks about all the changes that Evans underwent in his seven years in America. Like when he made it to the colonial Spanish stronghold in Louisiana. He stayed with them and ultimately changed his name to Don Juan Evans.

In addition to Evans’ Welsh tribal plans, he also did some mapmaking, including a thorough and impressive charting of the Missouri River. He is not really recognized for this but

his maps of the Missouri river were used by the American explorers Lewis and Clark, and he has some claim to have influenced the enduring outline of the US. The fact that Evans flew a Spanish flag above a former British fort, and stopped British Canadians from trading with tribes within Spanish territory, seems to have played a role in the fixing of a border between Canada and the US that could have lain much further south than where it ended up.

Both Evans and Rhys arrived at the Mandan village some two hundred years apart. Evans was welcomed and appreciated there. While “After 200 years of aggressive assimilation policies, two major smallpox outbreaks and two forced repatriations of the tribe Edwin Benton is the last speaker of the Mandan language.” Rhys shares donuts with him. Is it more disappointing that the Madogwys turned out to be a fantasy or that the Mandan language is now all but extinct.

Like John, Gruff spends the end of his tour in New Orleans. Evans died at the age of 29 (which is so hard to believe given all he accomplished). He had contracted malaria earlier and nearly died from it. Now he was back there and it was too much for him. Rhys survives, thankfully and plays many more shows.

Rhys’ epilogue is really beautiful, too.

Check out more about the book, the CD the movie and the app at the American Interior site.

Leave a comment