SOUNDTRACK: GREGORY PORTER-“Be Good (Lion’s Song)” (Field Recordings, May 14, 2013).

SOUNDTRACK: GREGORY PORTER-“Be Good (Lion’s Song)” (Field Recordings, May 14, 2013).

The still from this Field Recording [Gregory Porter: A Lion In The Subway] certainly led me to think that Porter would be singing on an actual moving train car (the ambient noise would be IMPOSSIBLE to filter out).

Of course, it wasn’t the most practical (or legal–bands and other musical acts need to audition to even set up underground. And those are just the “official” performers) thing to actually get Gregory Porter to perform on an operational MTA train. So we asked him if he’d perform for us at the New York Transit Museum in downtown Brooklyn, a collection of vintage memorabilia and reconditioned cars housed in a former subway station. All the better: Porter has a way with vintage suits, and there was a fortunate coincidence about the way it all felt right among the period-specific ads which flanked him. Accompanied by pianist Chip Crawford — who perfectly punches and beds the gaps here — Porter sang his original “Be Good (Lion’s Song),” a parable of unrequited affection.

The only thing I know about Gregory Porter comes from his Tiny Desk Concert. I marveled that he wore a hat with ear flaps the whole time. Well, he does the same thing during this song.

Gregory Porter has the frame of a football linebacker — maybe because he once was one, for a Division I college — and the rich, booming voice you might expect from a guy with such lungs. It cuts through a crowd with its strength, in the manner of an old-school soul singer; it demands attention with its sensitivity. If Porter weren’t winning over the international jazz club and festival circuit, he’d rise above the din wherever he went.

This is a sweet, quiet song, befitting him and the location. The lyrics are a clever metaphor about lions and love.

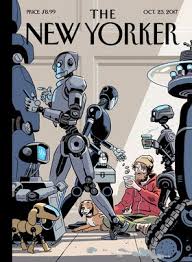

[READ: October 22, 2017] “Scared of the City”

This is an essay about being white in New York City.

Franzen says that in 1981 he and his girlfriend were finishing college and decided to spend a summer in New York City– a three-month lease on the apartment of a Columbia student on the comer of 110th and Amsterdam. It had two small bedrooms and was irremediable filthy.

The city seemed starkly black and white “when a young Harlem humorist on the uptown 3 train performed the ‘magic’ act of making every white passenger disappear at Ninety-Sixth street, I felt tried and found guilty of my whiteness.”

A friend of theirs was mugged at Grant’s Tomb (where he shouldn’t have been) and now Franzen was morbidly afraid of being shot. The impression of menace was compounded by the heavy light-blocking security gates on the windows and the police lock on the door.

Franzen made some money when his brother Tom came into the city to do some work for hot shot photographer Gregory Heisler at Broadway and Houston. Franzen was a gopher and made trips around the Bowery and Canal Street but he knew not to go to Alphabet City.

For fourth of July they went to East End Avenue to watch fireworks with a friend’s family. Her elevator opened directly in to the apartment’s front hall [the first time I saw such a thing, I was astonished too].

I appreciated Franzen’s honesty in this essay:

Under the spell of my elite college education, I envisioned overthrowing the capitalist political economy in the near future, through the application of literary theory. But in the mean time, my education enabled me to feel at ease on the wealthy side of the line.

He was too idealistic to want more money than he needed and too arrogant to envy the rich. They were more of a curiosity, “interesting for the conspicuousness of both their consumption and their thrift: They had lunch at Tavern on the Green (where you had to pay extra for a side vegetable) but one of the ladies’ shoes was held together with electrical tape.

Tom could have charged Heisler two or three times as much as he did, not realizing his value outside of Chicago. And Franzen himself left the city in debt, owing money to the hospital–there was glass in a bowl of soup that he ate and he needed stitches (why didn’t he sue the restaurant?) While in the hospital he saw a woman with a bullet hole in her abdomen–the very thing he lived in fear of.

Fifteen years later he bought a studio in a loft on 125th street. He jumped on a cheap place in Harlem because he wasn’t scared of the city anymore. He made friends with neighbors in Harlem and felt secure on the Alphabet streets. He eventually moved to the Upper East Side. He notes that the city’s dividing line had become more permeable in at least one direction: White power (not “white power”) asserted itself through the presence of real-estate prices and police action.

In hindsight the era of white fear seems most remarkable for having lasted as long as it did.

Of all my mistakes as a twenty-one-year old in the city, the one I now regret the most was my failure to imagine that the black New Yorkers I was afraid of might be even more afraid than I was.

It’s not easy to talk about racism, especially from a successful white male, but I think he handles this rather well.

Leave a comment