SOUNDTRACK: RHEOSTATICS-Music Inspired by the Group of 7 (1995).

SOUNDTRACK: RHEOSTATICS-Music Inspired by the Group of 7 (1995).

In music there’s always a… key in which the composition is set… In painting there’s a mother color that goes through all–it holds the painting together…you might call it the signature of the painting.

In music there’s always a… key in which the composition is set… In painting there’s a mother color that goes through all–it holds the painting together…you might call it the signature of the painting.

And thus opens the Rheostatics Group of 7 record. I had always been vaguely dismissive of the album because it is mostly instrumental and, while good, I just didn’t listen to it that much. After seeing it live it’s time for a reappraisal.

The disc opens with “One” a lovely minute-long piano introduction. It’s followed by “Two” which has a series of piano and guitar trills as they set a bucolic mood. Then the drums kick in. This song starts slowly with some plucked strings (and a sample from Queen Elizabeth). What I love about this piece is that after the trills, the song seems to build to a very cool cello riff (provided by drummer Don Kerr). Then there’s a vocal section (of bah bahs) which was really highlighted when they played it live.

The first highlight of this record for me is “Three,” which is known as the Boxcar song. Someone shouts “All aboard” as the chugging begins and the cello and drums keep an excellent rhythm with Martin’s amazing guitar melody. “Five” is another waltz with, to my ears, a vaguely Parisian sound. Martin sings a few verses (and a chorus of “blue hysteria”). It’s a lovely, delicate piece.

“Six” is a longer piece which centers around a slowly swirling guitar and cellos motif. It ends with some noisy moments and more rainfall. Until a noir sounding coda creeps up with piano and upright bass,.

Then comes “Seven” a cello based version of the awesome song “Northern Wish.” I prefer the original because it is so much more intense, but this quieter version is really interesting and subtle. “Nine” starts slowly with some gentle acoustic guitars. But it builds and grows more intense (it has the subtitle “Biplanes and bombs”). As the song progresses (around 3 minutes) Tielli’s guitar comes in and the backing notes grow a little darker. The last 15 second are sheer noise and chaos (live they stretched this section out for a while, and it was very cool to see Hugh Marsh makes a lot of noise with his violin).

“Ten” uses some nontraditional instruments including what I assume is a didgeridoo and all kinds of samples. On stage Tim and Kevin were swinging those tubes that whistle to make the noises).

Eleven is a reprise of track one, Kevin’s Waltz, with the vocals sung by Kevin Hearn.

I have really come to appreciate this album a lot more. It doesn’t have any of my favorite songs on it, but it is a really amusing collection fo songs.

[READ: August 20, 2015] The Group of Seven and Tom Thompson

I have had this book for a number of years. I’m not even sure where I got it (in hardback no less). I know that I purchased it because of the Rheostatics, because I had never heard of the Group of Seven before the band made their record inspired by them. Since I was going to see the paintings live, I decided to read up about the Group a bit more (I liked the paintings a lot, I just hadn’t read much).

Sadly, the Art Gallery of Ontario wasn’t open for viewing when we went to the concert (which makes sense as it was at night) and we didn’t have another opportunity to go to AGO. Fortunately, we also went to Casa Loma which had a room full of Go7 paintings, so I was delighted to see some of these up close. (They may have been prints, it was unclear, but it was cool seeing them).

So the Group of Seven were (initially) seven Canadian painters who joined together to create uniquely Canadian works of art from 1920 to 1933. Their art was meant to celebrate their country which they felt was under-represented in art. They planned to not follow conventional European styles of painting and often made striking scenes of nature. They are largely known for their landscapes, although they also painted portraits and other works.

The Group of 7 originally originally consisted of (links are to Wikipedia bios): Franklin Carmichael (1890–1945), Lawren Harris (1885–1970), A. Y. Jackson (1882–1974), Frank Johnston (1888–1949), Arthur Lismer (1885–1969), J. E. H. MacDonald (1873–1932), and Frederick Varley (1881–1969). Later, A. J. Casson (1898–1992) was invited to join in 1926; Edwin Holgate (1892–1977) became a member in 1930; and LeMoine FitzGerald (1890–1956) joined in 1932.

Two artists commonly associated with the group are Tom Thomson (1877–1917) and Emily Carr (1871–1945).

By 1920, they were ready for their first exhibition thanks to the constant support and encouragement of Eric Brown, the director of the National Gallery at that time. Prior to this, many artists believed the Canadian landscape was not worthy of being painted. Reviews for the 1920 exhibition were mixed, but as the decade progressed the Group came to be recognized as pioneers of a new, Canadian school.

What I rather liked about this book was the way it was setup. Rather than focusing on one artist at a time or even the subjects of the paintings, Silcox organized the book as a travelogue across Canada. Certain of the Seven worked in different locations more than others, so the book kind of works regionally and by artist, but it allows you to see that although these artists were a group creating a unique style, they also worked independently of each other.

Silcox’s essays are wonderful. They are brief but informative, blending fact and opinion about the group (Silcox is an art historian). But the highlight of the book is the artwork. It is lavishly reproduced with about 400 pictures, most of which are full page. The ones that aren’t are, I believe, actual size (the Group seemed to make postcard-sized prints).

The Group of 7 did not include Tom Thompson, who died before the Group formally convened. But the book includes many prints from Thompson and it is clear that he was an inspiration and kindred spirit.

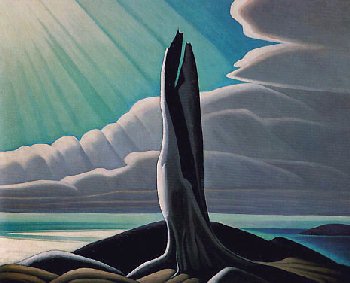

Of the formal Group, my favorite painter is Lawren Harris (left) who has such an unusual style. I find all of his works in this style to be mesmerizing to me. It is vaguely cartoonish and yet also very precise. The darks and lights are just amazing. It is called North Shore, Lake Superior (1928).

Of the formal Group, my favorite painter is Lawren Harris (left) who has such an unusual style. I find all of his works in this style to be mesmerizing to me. It is vaguely cartoonish and yet also very precise. The darks and lights are just amazing. It is called North Shore, Lake Superior (1928).

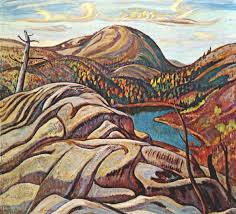

A.Y. Jackson (right) had a similar style of bold strokes and large lines, but his work was bit more melancholy to me. He served as a war artist during World War I and was asked to join the Group when Lawren Harris saw his neo-impressionist “The Edge of Maple Wood” and wanted to buy it (that’s not the painting to the right, which is called Nellie Lake (1933)).

A.Y. Jackson (right) had a similar style of bold strokes and large lines, but his work was bit more melancholy to me. He served as a war artist during World War I and was asked to join the Group when Lawren Harris saw his neo-impressionist “The Edge of Maple Wood” and wanted to buy it (that’s not the painting to the right, which is called Nellie Lake (1933)).

Franklin Carmichael (left) was the youngest member. He was based in Ontario for his youth, but he studied in Belgium briefly before the war. Despite being the youngest member of the Group, he was elected president of their affairs. He uses a style similar to the broad strokes, but he also includes some interesting tree shapes and forms, which I rather like. He seems to have a whole series of autumnal painting with lots of yellows and oranges. But I am drawn to this painting on the left (Mirror lake, 1929) which falls into the Harris mode. Perhaps I just like blues better than oranges.

Franklin Carmichael (left) was the youngest member. He was based in Ontario for his youth, but he studied in Belgium briefly before the war. Despite being the youngest member of the Group, he was elected president of their affairs. He uses a style similar to the broad strokes, but he also includes some interesting tree shapes and forms, which I rather like. He seems to have a whole series of autumnal painting with lots of yellows and oranges. But I am drawn to this painting on the left (Mirror lake, 1929) which falls into the Harris mode. Perhaps I just like blues better than oranges.

Frank Johnston (right) seems to use a slightly more realistic brush even as his paintings fit nicely into the group’ overall style. He was a commercial artist for a time. He met Lawren Harris at the Arts Letters Club, a group of a hundred men who would meet regularly to discuss conversation and art. The purpose of this group was to create a place where people with different interests could meet and discuss their own artistic creativity in many different arts. This painting is Moose Pond from 1918.

Frank Johnston (right) seems to use a slightly more realistic brush even as his paintings fit nicely into the group’ overall style. He was a commercial artist for a time. He met Lawren Harris at the Arts Letters Club, a group of a hundred men who would meet regularly to discuss conversation and art. The purpose of this group was to create a place where people with different interests could meet and discuss their own artistic creativity in many different arts. This painting is Moose Pond from 1918.

I rather like Arthur Lismer’s style as well (left). Lismer was born in England but emigrated to Canada when he was 26. I feel like his color palate is a little less exiting than Harris’ as he seems to have worked a lot in browns. I think perhaps he choice more pastoral works which tend to be less dramatic. This one is Cathedral Mountain from 1928.

I rather like Arthur Lismer’s style as well (left). Lismer was born in England but emigrated to Canada when he was 26. I feel like his color palate is a little less exiting than Harris’ as he seems to have worked a lot in browns. I think perhaps he choice more pastoral works which tend to be less dramatic. This one is Cathedral Mountain from 1928.

J.E.H. MacDonald (right) was also born in England. he came to Canada when he was a teen. has a big variety of works. Some of his paintings are practically pointillist (his paintings of flowers are almost hard to see the details in it). And yet, he also does some of the most realistic paintings of the group. Like this amazing painting to the right. I love that in 1918 and 1919 he and Lawren Harris financed boxcar trips for the artists of the Group of Seven to the Algoma region in Northeast Ontario.

J.E.H. MacDonald (right) was also born in England. he came to Canada when he was a teen. has a big variety of works. Some of his paintings are practically pointillist (his paintings of flowers are almost hard to see the details in it). And yet, he also does some of the most realistic paintings of the group. Like this amazing painting to the right. I love that in 1918 and 1919 he and Lawren Harris financed boxcar trips for the artists of the Group of Seven to the Algoma region in Northeast Ontario.

Frederick Varley was also born in England. Lismer (who went to England for Varley’s wedding) encouraged him to move to Toronto. He seems to have done more portraits than the other members and to me much of his work is kind of bleak looking. He did paint some lovely landscapes, but he also brought that Group of 7 technique into his portraits. Like this one on the left, Vera, 1931.

Frederick Varley was also born in England. Lismer (who went to England for Varley’s wedding) encouraged him to move to Toronto. He seems to have done more portraits than the other members and to me much of his work is kind of bleak looking. He did paint some lovely landscapes, but he also brought that Group of 7 technique into his portraits. Like this one on the left, Vera, 1931.

A.J. Casson joined the group later. After Frank Johnston left the group in 1921, Casson seemed like an appropriate replacement. Later in 1926, he was invited by Carmichael to become member of the Group of Seven. Ironically, in the same year he also became an Associate Member of the most conservative Royal Canadian Academy (the very type of Academy that was sp opposed to the Group’s work). His style is similar, and to me he seems to take their general aesthetic and push it somewhat. The vibrancy of the colors make his painting (right) almost hyper real. This one is called October (1928).

A.J. Casson joined the group later. After Frank Johnston left the group in 1921, Casson seemed like an appropriate replacement. Later in 1926, he was invited by Carmichael to become member of the Group of Seven. Ironically, in the same year he also became an Associate Member of the most conservative Royal Canadian Academy (the very type of Academy that was sp opposed to the Group’s work). His style is similar, and to me he seems to take their general aesthetic and push it somewhat. The vibrancy of the colors make his painting (right) almost hyper real. This one is called October (1928).

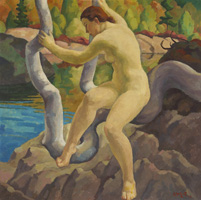

Edwin Holgate also did a lot of portraits. His family moved to Jamaica when he was three, but he was then sent back to Toronto when he was five to go to school. When he was nine his family moved back to Canada and settled in Montreal. He played a major role in Montreal’s art community. His landscapes are also quite lovely. He is mostly known for his nudes, both wood print and paintings, particularly for a number of female nudes in outdoor settings that he painted during the 1930s. like this one to the left, Early Autumn, 1938.

Edwin Holgate also did a lot of portraits. His family moved to Jamaica when he was three, but he was then sent back to Toronto when he was five to go to school. When he was nine his family moved back to Canada and settled in Montreal. He played a major role in Montreal’s art community. His landscapes are also quite lovely. He is mostly known for his nudes, both wood print and paintings, particularly for a number of female nudes in outdoor settings that he painted during the 1930s. like this one to the left, Early Autumn, 1938.

Lemoine Fitzgerald (right) brought the number of the Group of 7 up to ten. His style seems to diverge somewhat to me. His subject was more of his immediate surroundings—the view of the back lane outside his house; a potted plant on the windowsill. His style grew more spare and abstract over his career, especially after the group disbanded. His style seems more impressionist to me. This one is Figures in a Park, 1928.

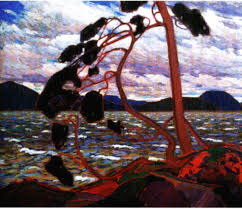

Tom Thompson (left) was the forefather to the Group, and you can see from his work how they were certainly inspired by him both in subject and in style. Thomson’s death is a little mysterious. He disappeared during a canoeing trip on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park on July 8, 1917, and his body was discovered in the lake eight days later.

Tom Thompson (left) was the forefather to the Group, and you can see from his work how they were certainly inspired by him both in subject and in style. Thomson’s death is a little mysterious. He disappeared during a canoeing trip on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park on July 8, 1917, and his body was discovered in the lake eight days later.

Emily Carr was never officially asked to join the Group (it was boys club for sure) but she was inspired by them and often worked with them. Reading about her was very interesting, and I’d like to learn more about her. I like that she diverged in subject matter somewhat from the others, including this one of totem poles.

Emily Carr was never officially asked to join the Group (it was boys club for sure) but she was inspired by them and often worked with them. Reading about her was very interesting, and I’d like to learn more about her. I like that she diverged in subject matter somewhat from the others, including this one of totem poles.

When I paint I tend to do very realistic pictures. It’s a style I like and which I am good at. And yet I love these more abstract works so much. And I am envious that I don’t seem to be able to do them. I need a class in how to see like Lawren Harris.

Leave a comment