SOUNDTRACK: GORD DOWNIE AND THE COUNTRY OF MIRACLES-The Grand Bounce (2010).

SOUNDTRACK: GORD DOWNIE AND THE COUNTRY OF MIRACLES-The Grand Bounce (2010).

I knew I was going to write about Canadian musicians for this series of Extraordinary Canadians, but I wasn’t sure who would get matched to whom. I figured I’d match Gord Downie to Mordecai Richler, but when I saw this in the liner notes to this disc, I knew I’d made the right choice:

I knew I was going to write about Canadian musicians for this series of Extraordinary Canadians, but I wasn’t sure who would get matched to whom. I figured I’d match Gord Downie to Mordecai Richler, but when I saw this in the liner notes to this disc, I knew I’d made the right choice:

Thank you to the Richler Family for the font you are presently reading. The Richler font, not publicly available, was created and named for the great Mordecai Richler. It was commissioned by Louise Dennys, designed by Nick Shinn and graciously made available by Florence Richler. I am grateful for this honour.

So Gord Downie is the driving force behind The Tragically Hip. I’m always curious when a guy who pretty much runs a band needs to do a solo album (or three). And in this case, since the last Hip album was much more mellow and almost country, it seemed like he got some of his less rocky side out on that disc, so what’s the need? Unless, of course, it’s just the need to play with some other folks once in a while.

Well, whatever the reason, this disc finds Downie in incredible form. In fact, I think I like this disc better than the last Hip disc (which I did like, but which was a little too mellow overall). The songs are all great, from the simple folk tracks to the more elaborate rockers. And, yes, while the disc never rocks as hard as some Hip songs tend to, this is not a simple acoustic guitars and solo vocals record.

“The East Wind” is a wonderful starter. It’s fairly simple with awesomely catchy lyrics. I learned that the lyrics are from a quote by Todd Burley. And they are an awesome way to describe a hostile and violent wind: it’s lazy, because “it doesn’t go around you, it goes right through you.” Fantastic.

“Moon Over Glenora” sounds a lot like a Hip song. Downie’s lyrics are almost mumbled and understated until he gets to the end of each verse when he raises his voice an octave for maximum effect. The stops and starts in the bridge are also great. “As a Mover” is also smoothly catchy with a wonderful rising chorus.

“The Dance and the Disappearance” is another great conceit. This song is inspired by a quote from Crystal Pite: “Dance disappears almost at the moment of its manifestation.” It is suitably dramatic with some great verses. “The Hard Canadian” is a gentle acoustic number that would not be out of place on the more recent Hip records. “Gone” feels like a continuation of “Heart,” almost like the slightly more rocking second half of it.

My favorite track is “The Drowning Machine” (I seem to like anything that Downie writes that’s about the sea). It’s a minor chord wonder, dark and mysterious and wonderfully catchy. The rock comes back on the rather simple “Night is For Getting.” It’s probably the least essential track on the disc except that once again the chorus/bridge is really great and memorable.

The last three tracks bring on the mellow, which is a fitting ending for the disc, although since the three t racks take up about 12 minutes, it makes the end drag a bit. “Retrace” is a country-tinged (steel guitar) mellow track (again, Downie’s voice brings out the excitement) . “Broadcast” has an extended outro of gentle guitars and piano that for all the world sounds like the end of a disc, so I’m always surprised that there’s a final track after it. And so the final track “Pinned” feels like filler. It has a movie projector clicking sound and gentle piano with almost inaudible vocals. It’s actually a pretty song, but it feels almost discarded here.

One of things I’ve always liked about Downie’s lyrics is that they are atypical of rock songs. They’re not “about” sex or rock or drugs or swagger or anything like that. In this case they are about locations and events. And it really paints a picture. And speaking of painting, Downie painted the cover art. The beautiful simplicity of the painting is not unlike the beautiful simplicity of the music on the disc.

Oh and my copy is autographed too! (although I wasn’t there when he autographed it, so it could have been anyone who scribbled on the cover).

[READ: November 15, 2010] Mordecai Richler

I don’t know a lot about Mordecai Richler, although I feel like whenever I read about him it’s in hushed tones (a neat trick, that). Nevertheless, for a number of reasons I have wanted to read him for many years but have just never done it. Now, the stars are aligning with me for Richler.

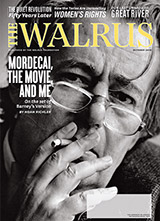

There’s this book, there’s the cover of the October 2010 issue of The Walrus and the recent filming of his book Barney’s Version (the filming of which is discussed in the same issue). And then a patron asked for the film of The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz. So, it’ about time to read one of his books. But here’s the rub…do I start with the great books or do I start at the beginning and work my way through his career? And, there’s also a huge new biography coming out (the review of which mentions a wonderfully offensive event in which Richler absolutely dismisses his Jewish audience).

There’s this book, there’s the cover of the October 2010 issue of The Walrus and the recent filming of his book Barney’s Version (the filming of which is discussed in the same issue). And then a patron asked for the film of The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz. So, it’ about time to read one of his books. But here’s the rub…do I start with the great books or do I start at the beginning and work my way through his career? And, there’s also a huge new biography coming out (the review of which mentions a wonderfully offensive event in which Richler absolutely dismisses his Jewish audience).

This book was written by M.G. Vassanji. I feel that I’ve heard of him but I’ve never read him. And yet listen to this incredible biography:

M.G. Vassanji was born in Kenya and raised in Tanzania. He attended University in the United States, where he trained as a nuclear physicist, before coming to Canada in 1978. Vassanji is the author is six novels and two collections of short stories…and he has twice won the Giller Prize.

Damn.

Since I read this right after Coupland’s McLuhan it’s tempting to compare them. And yet, as I said in that review, it seems quite apparent than Coupland’s book will be like no one else’s, so I won’t say much about that. Instead, Vassanji opens the book by talking about the similarities between himself and Richler and their few awkward but pleasant meetings. (In this respect yes, it is sort of like Coupland’s book in that the author puts himself into the text).

For all of his Canadianness–his books are perpetually set in Montreal–Richler was really quite the globetrotter. He just couldn’t escape from the grips of his upbringing. And so, even though his books were written in other countries, he remains a preeminent Canadian writer.

Richler grew up as a Jew in the “ghetto” of Montreal where all the orthodox Jews lives (fighting with the nearby French but despising the controlling WASPs). He comes from long line of Rabbis (which is both a religious and writerly pursuit) and yet he was dismissive of the chruch from an early age. This may have had something to do with the fact that the super religious side of his family was his mother’s and he did not get along with her. She, likewise, did not get along with Mordecai’s father. Their marriage was annulled (!) when Mordecai was very young and his father was seen by many (even in his own family) as a pushover, a wimp, a pathetic man.

So naturally the writer in Mordecai gravitated towards him; in his later works, his father would be well-represented in a favorable light (whereas his mother would hardly be represented negatively if at all and his mother’s father (the Rabbi)–with whom he had a shocking falling out ) is practically the devil).

So naturally the writer in Mordecai gravitated towards him; in his later works, his father would be well-represented in a favorable light (whereas his mother would hardly be represented negatively if at all and his mother’s father (the Rabbi)–with whom he had a shocking falling out ) is practically the devil).

In Richler’s early post-college life, he went to Paris (and then seemingly the rest of Europe) to write. He sponged off his father (and his mother) while preparing his first book. And the stories of mild decadence and pouty behavior are quite enjoyable (letters to and from home are quoted in the text and are rather amusing). That first book was never published, but he edited it down and changed the focus. That rewrite was eventually published (with some censoring as his first book The Acrobats. If Richler’s ego needed a boost, this was it. For he was now a Published Author.

The rest of the biography follows his writing life–his early novels, his massive success with The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, and his later controversy-courting non-fiction essays. His success was good but not great–his fame was larger than his bank account. And he always sought ways to make more money for his ever-increasing family–most of whom were born and raised in England.

The rest of the biography follows his writing life–his early novels, his massive success with The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, and his later controversy-courting non-fiction essays. His success was good but not great–his fame was larger than his bank account. And he always sought ways to make more money for his ever-increasing family–most of whom were born and raised in England.

In the 1970s, he decided it was time to pick up stakes and return to Canada. His family–most of whom were quite comfortable in England–was uprooted, but his return was heralded, and he became a literary statesman.

The one thing that I didn’t like about the book is that it felt like Vassanji was repeating himself quite often. The entire early part of the biography deals with Richler’s Jewishness. And yet in the later chapter The Haunted Jew, we relive his strict Jewish upbringing, event for event that we read earlier. It’s simply weird, as you read the same story, you expect a new twist to be added, but you don’t get one. It’s just the same details again.

There were several other examples where a retelling of events was presented in a new chapter. It’s only really surprising because the book is quite short and he obviously has a lot of stories about himself. Aside from that flaw, Vassanji’s biography is a solid, enjoyable story.

Richler is a fascinating figure: controversial in both his fiction and his non-fiction. But Vassanji looks past the controversy at the man himself and the contents of his books. He never quite manages to make him sympathetic (which is probably for the best, as it seems like Richler didn’t want to be seen that way), but he makes me really want to read his works.

And isn’t that what a biography (of an author) should do?

And here’s a shameless plug to the folks at Penguin Canada–I will absolutely post about all of the books in this series if you want to send me the rest of them. I don’t know how much attention these titles will get outside of Canada, but I am quite interested in a number of the subjects, and will happily read all of the books if you want to send them to me. Just contact me here!

Leave a comment