SOUNDTRACK: SINÉAD O’CONNOR-The Lion and the Cobra (1987).

SOUNDTRACK: SINÉAD O’CONNOR-The Lion and the Cobra (1987).

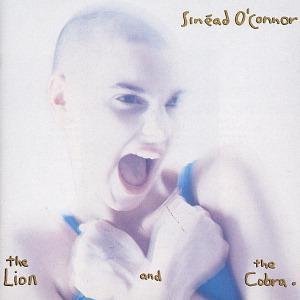

I was tempted to say that this album came before all of the controversy. But then, she’s always had controversy around her. Just the fact that she had her head shaved was enough to incite some people to alarm (not to mention, we never received this more fierce looking album cover).

I was tempted to say that this album came before all of the controversy. But then, she’s always had controversy around her. Just the fact that she had her head shaved was enough to incite some people to alarm (not to mention, we never received this more fierce looking album cover).

But before all of the success of “Nothing Compared 2 U,” she released this amazing, empassioned debut album.

I’ve no idea what the first track is about, but there’s something about her voice on the “oh’s” in particular that still gives me chills. “Mandinka” has a great guitar sound (seemingly destined for hit radio) that seems very out of place on this disc (again, I’m lost on the lyrics here, too).

The album comes into its own with the really odd but delightful “Jerusalem.” Musically it’s got a sort of funk base which resolves itself into a very winning chorus. And, once again, her voice sounds otherworldly. It’s followed by the largely acoustic “Just Like U Said it Would B” (Prince fan much?). It’s a fairly simple song (with interesting arrangement–I like the flute) that builds to a strong climax.

“Never Get Old” opens with some spoken Irish (and features future star Enya), but it’s “Troy” that is the absolute breakthrough on this disc. From the occasionall string swells, to the eerie silences to the incredible heights that she reaches (and the notes that she can hold) it’s really tremendous.

“I Want Your Hands on Me” seems like another grab for a single. The single version featured a bizarre little rap from MC Lyte. In the pantheon of silly rap lyrics, I’ve alwys kept this near the top: “I’m not the kind of girl to put on a show coz when I say no, yo I mean no.” Sentiment and good intentions aside, it’s very clumsy. Not my favoite track.

The final two, “Drink Before the War” and “Just Call Me Joe” are interesting denouements after the pop of “Hands.” “Drink is a slow paced, somewhat quiet track, until the chorus really blasts off. And “Joe” sounds like a demo: a raw electric guitar, cranked way up (but mixed quietly) accompanying Sinéad’s instructions to just call her Joe.

In some ways this album is less subtle, and by that reckoning, less sophisticated, than the bajillion-selling follow up, but I find the naked passion on this disc to be even more amazing.

[READ: Week of August 30, 2010] Ulysses: Episodes 18

The final chapter of Ulysses is all about Molly. It enters her head and doesn’t leave. It doesn’t even pause for punctuation (there’s none in the entire chapter except for the final period). There are paragraph breaks, which means that there are eight sentences in total.

The Episode is crass and sexual, beautiful and moving, personal and insightful and it seems incredibly forward thinking coming from a male writer. And although it gets a lot more press as a stream of consciouness piece, it’s not that far removed from Stephen’s or Bloom’s pieces, [except that she doesn’t actually intearct with anyone to interrupt her thoughts].

The Epsiode reflects upon what we’ve learned in the day. It inadvenrtanetly corrects some misperceptions (regarding Molly’s past infidelities–she didn’t have any–), but it also shows some pretty poor judgments on Molly’s part (mostly regarding Stephen). And there’s just so much going on in the episode that it’s hard to catalog it all. But it is certainly full of a lot of sexual thoughts.

The scene opens with Molly annoyed that Poldy has asked her for breakfast in bed tomorrow (which, we note he did for her this morning). She’s also annoyed that he woke her up because she’s sure she won’t get back to sleep.

It was she who told Poldy about Dignam’s funeral, and when she showed him the paper, he covered up the letter to his “pen pal,” thinking she didn’t know what he was up to. But she’s been suspicious of his affairs for some time. [There’s no evidence that he had any affairs, I don’t think. Even the letters to Martha show that they haven’t met yet (or if they really intend to).

Sex. And confession. (A good joke about telling the priest where he touched her: “On the canal bank”). But also a good point about the priest drawing out the questions, almost as if in titillation for himself. Oh, and Boylan is a massive stallion compared to Bloom with a “big red brute of a thing” (“though his nose is not so big”) (611).

But even during this fond reminisncence of Boylan’s massive amount of spunk, she changes direction and wonders what men would think if they had to have the babies (look at poor Mrs Purefoy there). And some men just aren’t worth it. There’s one who goes to bed with his muddy boots on. And crazy Mr. Breen is looking for £10,000 because of the U.p.: up postcard (official meaning of the postcard unresolved as far as I can tell).

She admits to herself that she’s never marry another man, and, if she’s honest, he got pretty lucky to find her.

In the second paragraph, she thinks about how different her “admirerers” are. And this pretty much undermines what Bloom thought about Molly’s previous lovers (whether he believed it or not is another question), Bartell D’Arcy, among others. She speaks a lot of kissing but it appears that she never had sex with any of them.

And then, in another nice piece of daylong synchronicity, we learn that it was Molly who threw the penny out of the window to the beggarman in the street [in Epsiode 10: A plump bare generous arm shone, was seen, held forth from a white petticoatbodice and taut shiftstraps. A woman’s hand flung forth a coin over the area railings. It fell on the path.] (and the Dedalus girl was the urchin who picked it up for him).

She coments on Bloom’s underwear fetish (which we witnessed every time he picked up her clothes) and observes that girls in Gibraltar often didn’t wear any underwear. She’s also put off by Blazes’ rage at losing a bet on the race (because of Lenehan’s tip–who would think such a Throwaway joke would have such staying power?).

But still, Blazes is passionate. And Molly can’t wait to see him again. She wishes she could lose weight and dress better for him. Of course that would mean that Bloom would have to make more money:

he ought to chuck that Freeman with the paltry few shillings he knocks out of it and go into an office or something where hed get regular pay or a bank where they could put him up on a throne to count the money all the day (619).

She then thinks of her breasts and how Blazes sucked on them for so long. She also remarks on how much more beautiul they are than penises (his two bags full and his other thing hanging down out of him or sticking up at you like a hatrack no wonder they hide it with a cabbageleaf (620)). There’s a mark on one of her breasts where Poldy bit her (!). But after Milly was born, her breasts were so hard she had to have him suck on them (he said she should just milk their tea with the excess).

Poldy also thought that Molly should pose nude for photos (and we understand that he has a small collection of nude photos, so he would know). Amusingly she thinks she should write a book of all the weird things that Poldy says (which of course harkens back to Haines and Stephen in Episode 1). Then she shifts back to Blazes and the amazing orgasm she had with him”

tickling me behind with his finger I was coming for about 5 minutes with my legs round him I had to hug him after O Lord I wanted to shout out all sorts of things fuck or shit or anything at all only not to look ugly (621).

And she can’t wait to see Blazes again.

Paragraph four opens with a train whistle which hearkens back to her childhood in Gibraltar. I admit this paragraph didn’t grab me as much, although there’s an amusing part about her writing herself letters because she was so bored. She wishes that she could get love letters again. And, as the paragraph ends she sighs a lament:

its all very fine for them but as for being a woman as soon as youre old they might as well throw you out in the bottom of the ashpit (624).

The fifth paragraph has her reflecting back on previous love letters (Lt. Mulvey was the first). There’s more reminiscences of her Spanish childhood (and the first appearances of Spanish words, I believe): “leave me with a child embarazada” (626). She thinks back to early romances:

I pulled him off into a handkerchief pretending not to be excited…I made him blush a little when I got over him that way when I unbuttoned him and took his out and drew back the skin it had a kind of eye in it” (626).

She wonders where Mulvey would be now (its nearly 20 years later). She wonders if he’s married now.

She thinks that Bloom (youre looking blooming Josie used to say (626)) is a better name than Breen or Briggs or “those awful names with bottom in them Mrs Ramsbottom or some other kind of bottom” (626). She even toys with the idea of divorcing Bloom to take the name Boylan, and then wishes her mother had named her better.

In a nod back to Episode 8 when Bloom is talking to Mrs Breen (and he talks about women being cruel to each other), she thinks about Kathleen Kearney:

and her lot of squealers Miss This Miss That Miss Theother lot of sparrowfarts skitting around talking about politics they know as much about as my backside anything in the world to make themseles someway interesting (627).

And as the paragraph ends, she tries to hold back a fart (so as not to wake Poldy) but when the train whistle goes off again, she lets it out.

Paragraph six sees her pleased with herself for not holding it back: “wherever you be let your wind go free” (628). She thinks about being nervous at night now that Milly is out of the house, but she’s aware of why Poldy sent her away “on account of me and Boylan thats why he did it Im certain” (630). She thinks about Milly and how much she has changed from when she was little (She could smell the cigartettes off of Milly’s clothes when she mended them). And she has had to chastise Milly for revealing too much (much like her mother no doubt did as well).

She thinks again about money and wonders if she’ll ever have a proper servant again (one that doesn’t get hit on by Poldy, or one like Mrs Fleming who you had to clean up after she cleaned up).

Then she thinks about Stephen (“who got all those prizes for whatever he won them in” (633)). And she’s embarassed that Poldy brought him home when her knickers could have been lying around.

Then she realizes she’s getting her period and knows that she’s not pregnant from Blazes (for better or worse).

O patience above its pouiring out of me like the sea anyhow he didn’t make me pregnant as big as he is I don’t want to ruin the clean sheet I just put on I suppose the clean linen I wore brought it on too damn it damn it and they always want to see a stain on the bed to know youre a virgin for them all thats troubling them. (633).

She thinks of shaving her pubic hair “wouldnt he get the great suckin the next time he turned up my clothes on me id give anything to see his face” (633). And then in a play on the Nighttown sequence, Molly, after feeling how smooth her thighs are wishes that she could be a man “God I wouldnt mind being a man and get up on a lovely woman” (633).

Molly climbs back into bed and she laughs about her past with Poldy (and his strange habits: look at the way hes sleeping at the foot of the bed…its well he doesnt kick or he might knock out all my teeth” (634). She gets grumpy about him again though when she thinks about all the times they moved (and how it was always for lack of money). Or about his lies “I suppose he thinks I dont know deceitful men all their 20 pockets arent enough for their lies then why should we tell them even if its the truth they dont believe you” (635.)

She thinks sadly of Rudy, and how he’d be 11. And then thinks of the men at Dignam’s funeral. She knows them all. But she feels that they think they are superior, even if they all have their secrets (Tom Kernan that drunken little barrelly man…Jack Power keeping that barmaid he does” (636). And then she gets defensive of Poldy:

theyre a nice lot all of them well theyre not going to get my husband again into their clutches if I can help it making fun of him then behind his back i know well when he goes on with his idiotics because he has sense enough not to squander every penny piece he earns down thier gullets and looks after his wife and family goodfornothings poor Paddy Dignam all the same (636).

The she thinks about all the young men she’s seen bathing at the rocks. And then of Stephen again. She thinks he must be about 20

Im not too old for him if hes 23 or 24 I hope hes not that stuckup university student sort [strike 1, Molly]…I hope hes not a professor like Goodwin [strike 2, Molly (sort of)]… hed be so clean compared with those pigs of men I suppose never dream of washing it from 1 years end to the other [oh, sorry, Molly, strike 3] (638).

And she thinks that she should read and become smarter so that Stephen will like her more.

In the final paragraph she criticizes Bloom again for his lack of manners and lack of refinement and the pulling off of trousers expecting you to admire it. Although she admits again she wishes she had one just once to see what it felt like “Swelling up on you so hard and at the same time so soft when you touch it” (638).

She is jealous that men can pick up whomever they want: single or married. And she imagines going to the the seaside and picking up “a sailor off the sea that be hot on for it and not care a pin whose I was ” (639).

She thinks sadly of Rudy again and how she shouldn’t have buried him in those clothes…give them to some poor child, but she pushes that thought away so as not to get gloomy.

She shifts back to Stephen and imagines him living with them (Poldy can make breakfast for 2, why not).

But she sours on Bloom again:

Ill know what Ill do Ill go about rather gay not too much singing a bit now and then mi fa pieta Maestro then Ill start dressing myself to go out presto non son piu forte Ill put on my best shioft and drawers and let him havea good eyefulout of that to make his micky stand for him Ill let him know if thats what he wanted that his wife is fucked yes and damn well fucked too up to my neck nearly not by him 5 or 6 times handrunning theres the mark of his spunk on the clean sheet…(641).

Then she blames him for what happened today:

Ive a mind to tell him every scrap and make him do it out in front of me serve him right its all his own fault if I am an adulteress…if he wants to kiss my bottom Ill drag open my drawers and bulge it right out in his face as large as life he can stick his tongue 7 miles up my hole as hes there my brown part then Ill tell him I want £1 or perhaps 30/- (641).

She calms down and realizes she’s not like other women: she doesn’t w nt to soak him for all of his money. And she treies to settles herself by counting. But she gets to five and is off on another thought.

As she drifts off to the end she thinks fondly of that day on Howth head when he proposed [and I’m quoting here all of the letters in the A House video that was mentioned in the comment of last weeks’ post–the letters that scroll on the bottom left read:]

like now yes 16 years ago my God after that long kiss I near lost my breath yes he said was a flower of the mountain yes so we are flowers all a womans body yes that was one true thing he said in his life and the sun shines for you today yes that was why I liked him because I saw he understood or felt what a woman is and I knew I could always get round him and I gave him all the pleasure I could leading him on till he asked me to say yes and I wouldnt answer first only looked out over the sea and the sky I was thinking of so many things he didnt know of (643).

And this recollection is quite stunning and majestic. And the passion is perfectly suited to the stream of consciousness style.

[And the video includes the text right up to the end]:

and I thought well as well him as another and then I asked him with my eyes to ask again yes and then he asked me would I yes to say yes my mountain flower and first I put my arms around him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes. (644).

And wow. That’s a lot of thoughts.

COMMENTS

Molly’s soliloquy is pretty amazing. It’s very real, and quite believable. She turns so many ideas over in her head from her own to her husband’s inadequacies. She justifies her behavior and feels somewhat smug about her affair even while she remembers so powerfully the day she said yes to him.

She also adds some perspective on the rest of the day. She talks about things that we didn’t really see (and she couldn’t have seen either), and although her accuracy is not always spot on (boy does she have Stephen wrong), she’s pretty aware of what’s going on from the people she has actually encountered.

This last chapter doesn’t add a great deal to the overall propulsion of the book (she ties up very few loose ends), but that is pretty much the modus of the book: the events of a single day. If you look at a single day in anyone’s life, you can’t know what happens on the next day. Even if they say something will happen, it may not.

And this, for better or worse, introduces us to modern literature, and modern literature’s propensity towards “unfinished” stories.

In terms of this being #1 on the MLA list, it is quite obvious that this book has practically foreshadowed the future of literature. It delves into literature’s past and shows what literature would look like after it. It’s not an easy book. It’s not always an enjoyable book. Sometimes, it depends on so much foreknowledge, that it makes you feel like an idiot.

And yet, it offers some of the most fully developed characters in literature. If you met Stephen or Leopold or even Molly on the street, you would likely know exactly what they’d say or how they’d react. And, I also have to say that it is a very modern (in many senses of the word) account of womanhood.

Good on ya.

POSTSCRIPT: I am currently listening to Ulysses on audio book. (I’m in Episode 10). I am finding this second go through to be very helpful (especially on the heel of just reading it). But moreso, I find the audio is really helpful for getting through some tough scenes. The ambiguity is more or less removed. The Joyce family estate gave the actor a guide for how to pronounce and what kind of emphasis to put on the words. And, of course, he has a different voice for Bloom’s interior monologue as for his speaking monologue. And that alone changes a lot of how you hear the book.

I’ll give occasional updates until I finish the audio book to see what else I have picked up and what other connections I have made.

For ease of searching, I include: Sinead O’Connor

You pee up. It’s juvenile, but it has the desired effect of pissing off the recipient.

Maybe more later. Lovely post.

Is it really that simple? (childish but amusing, but surely not worth libeling someone over–unless Breen is just nuts). I keep looking for something deeper in it.